Poland’s Private Credit Landscape

Poland's private credit market is characterised by strong demand, evolving regulations, and a variety of lending segments.

Role of Non-Bank Financial Institutions (NBFIs)

- Consumer loan companies

- Leasing firms

- Fintech platforms

These institutions are increasingly vital in addressing the credit requirements of households and small businesses, particularly in regions where traditional banks may fall short.

Focus of This Report

This analysis examines:

- Macroeconomic backdrop of Poland.

- Regulatory environment shaping the private credit sector.

- Key lending segments driving market activity.

- Major market players across different product lines.

- Risks and opportunities for investors considering private credit deals in Poland.

The Big Picture: Poland’s Macroeconomic and Private Credit Overview (2019–2024)

Economic Growth and Challenges

- Poland has been one of Europe’s growth standouts over the past decade.

- Post-pandemic rebound: Real GDP surged +6.9% in 2021 and +5.3% in 2022.

- Slowdown in 2023: Growth fell to ~0.2% amid high inflation and spillovers from the war in Ukraine.

- 2024 recovery: Growth regained momentum (~3% YoY) as inflation cooled and investment activity picked up.

Table 1 — Core Macroeconomic Indicators: Poland

Key Takeaways

Poland avoided a deep COVID contraction; GDP in 2023 was 14% above the pre-pandemic level.

The 2022-2023 inflation spike (14.4%) was driven by energy and food; inflation is now projected to fall below 4% in 2024.

Fiscal deficit doubled to 5.3% of GDP in 2023 and remains structurally high.

The current account shifted from a deficit (2022) to a surplus (2023) as energy imports normalised.

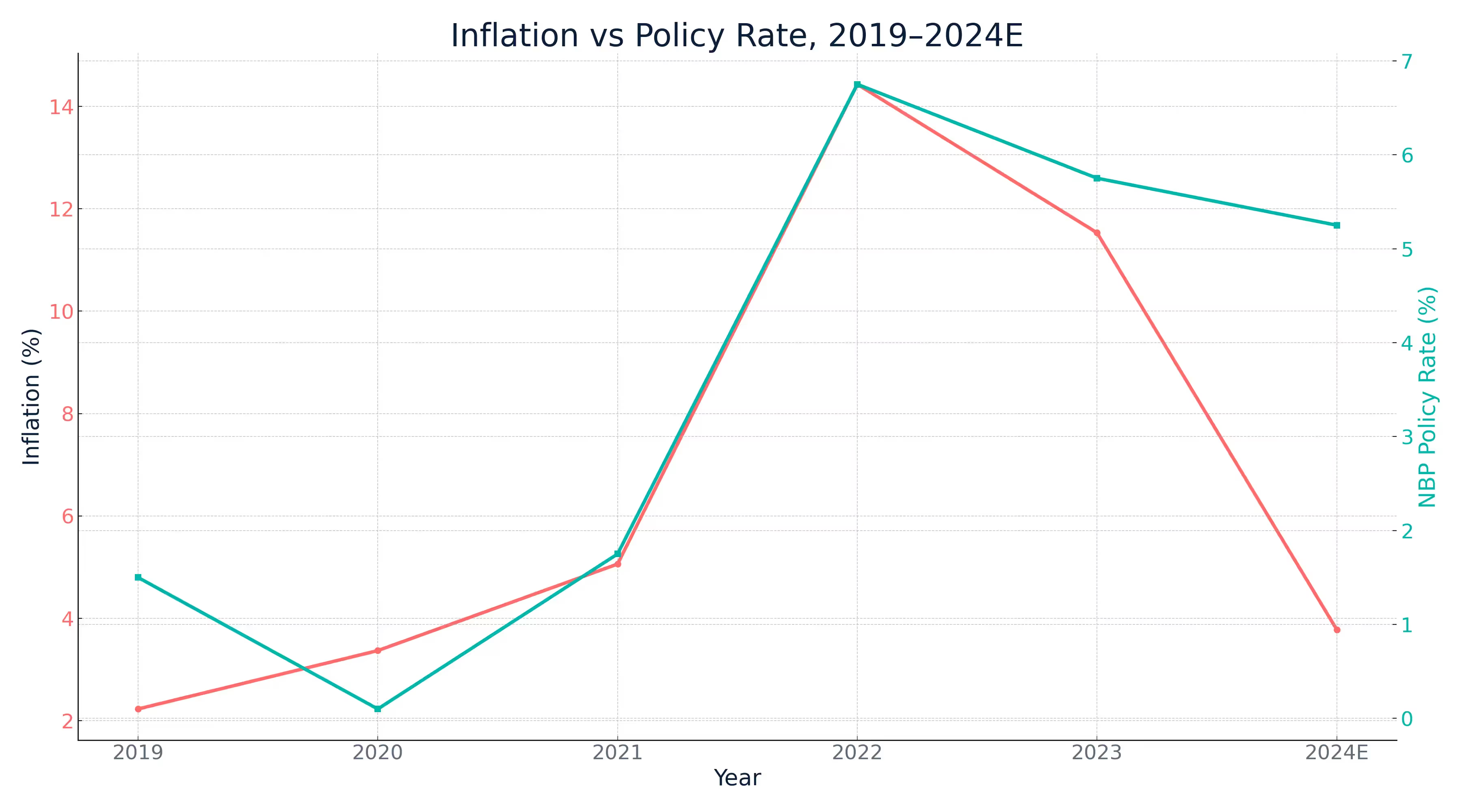

Inflation and Interest Rates

- Pre-2020: Stable low inflation (~3–5%).

- 2021–2022: Inflation surged, peaking above 17% — among the highest in the EU.

CPI averaged 14.4% in 2022 and 11.4% in 2023. - 2024: Inflation eased to ~3.9% as global energy pressures subsided.

- Policy response:

- NBP raised rates from ~0% in 2021 to 6.75% in mid-2022.

- Began cautious easing in 2024–2025, cutting rates to 5.25% by May 2025.

Impact: Borrowing costs surged during the tightening cycle, then eased slightly as inflation receded.

Table 2 — Fiscal & Monetary Indicators

Policy Context

- Debt is cushioned by a strong nominal GDP but is now near the EU early-warning threshold.

- After a 690 bp hiking cycle, the MPC cautiously shifted toward easing.

- Zloty rebounded to 3.7–3.9 PLN/USD, reduced imported inflation but pressured exporters.

Employment and Wages

- Pre-pandemic: Record-low unemployment (~3% Eurostat measure).

- COVID shock: Small uptick in 2020, quickly reversed.

- 2022–2023: Very tight labour market — official jobless rate ~5% (national definition) or <3% (international standard).

Trends:

- Rising wages and an influx of Ukrainian refugees partly offset shortages.

- Real wages fell in 2022 (inflation > wage growth).

- By 2024, real wages grew again, restoring purchasing power and supporting loan demand.

Credit Demand Environment

- Overall credit growth has been moderate.

- Bank lending slowed in 2022–2023 due to high rates and tighter rules.

- Consumer & SME demand persisted for short-term loans.

- NBFIs stepped in to provide unsecured and flexible lending options.

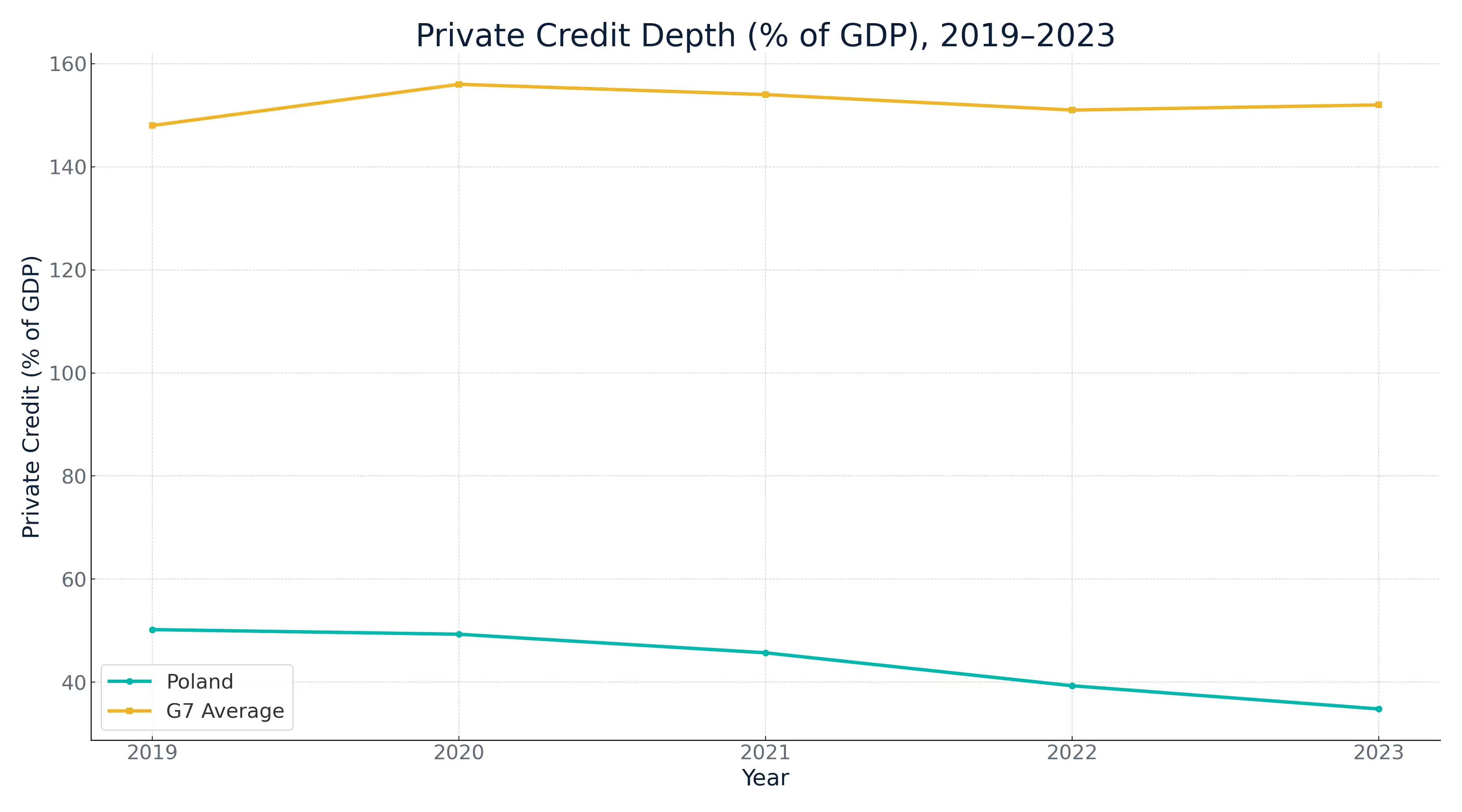

Table 3 — Private Credit Depth (% of GDP)

Interpretation for Investors

- Poland’s credit-to-GDP ratio fell 15 pp since 2019, reflecting bank deleveraging.

- At ~35% of GDP, it is just one-quarter of the G7 norm, signalling under-penetration.

- Creates space for growth in MFIs, leasing firms, BNPL, and auto lenders.

Risks & Opportunities – Interpreting the Numbers

Macro Tailwinds (Tables 1–2)

Cooling inflation and easing rates → boost disposable income, cut debt-service burdens.

Implications for NBFIs:

Lower impairment charges.

Ability to re-price loans at stable spreads as costs decline.

Structural Gap (Table 3)

- Conventional bank credit is scarce.

- MFIs, leasing firms, and BNPL platforms can expand without system over-leverage.

- For investors: Scalable opportunities with attractive yield/risk balance.

Illustrative Investment Opportunities

Regulatory Framework for Non-Bank Lenders (NBLs) and Multi-Finance Institutions (MFIs)

1. Overview

Poland has tightened regulations for non-bank lending institutions (NBLs and MFIs) in recent years, following EU-wide consumer protection trends.

- Key Law: Consumer Credit Act (Ustawa o kredycie konsumenckim, 2011).

- Major Amendment: “Anti-usury” package (late 2022).

- Principal Regulator: Polish Financial Supervision Authority (KNF / PFSA).

2. Licensing and Registration

Number of institutions: 534 registered as of mid-2024.

3. Supervision and Oversight

Before 2024

- KNF only maintained the register.

- Abuses were handled by UOKiK (competition/consumer office) or courts.

After January 2024

KNF Powers Expanded:

- Conduct audits for compliance.

- Issue binding recommendations.

- Impose sanctions and fines:

- Up to PLN 15 million per company.

- Up to PLN 150,000 per board member.

- Reporting obligations: Quarterly and annual submissions (loan volumes, revenue, funding sources).

- Supervision fee: Up to 0.5% of loan revenues (minimum €5k).

Impact: NBFIs now face bank-like regulatory scrutiny, though without deposit-taking rights.

4. Consumer Protection: Interest Caps

Effect: Traditional high-APR payday loans are no longer viable.

5. Loan Rollovers and Creditworthiness

- Rollovers: Costs from subsequent refinancing now count toward caps → prevents serial debt traps.

- Creditworthiness checks:

- Lending to a borrower with a negative assessment is prohibited.

- Standards for assessments are codified in law.

- Penalties:

- Violations may void loan contracts.

- Misrepresentation or falsified data = criminal liability:

- Fines up to PLN 1 million.

- Potential imprisonment.

6. Key Takeaways

Poland’s regulatory framework has shifted toward strict consumer protection and higher compliance costs.

Key features:

- Higher capital and governance barriers.

- KNF supervisory powers with significant sanctions.

- Stronger caps on loan pricing.

- Enforceable creditworthiness and reporting rules.

Result: Regulated similarly to banks, NBFIs primarily secure funding through equity or wholesale debt, rather than deposits.

Structure and Size of Poland’s Non-Bank Lending Sector

Poland’s non-bank lending sector is diverse, covering:

- Traditional personal loan companies

- Specialised leasing and factoring firms

- Emerging fintech lenders (BNPL providers)

- Multi-finance institutions

Although banks continue to hold the largest share of credit (approximately 74% of financial system assets), non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) are crucial in bridging significant market gaps.

This analysis will delve into the primary segments: cash loans, leasing, Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL), and car loans, examining their scale, structure, and key participants.

1. Cash Loans (Consumer Installment and Payday Loans)

Market Scale

- Q1 2024: PLN 6.59 billion in consumer credit (+113% YoY).

- PLN 4.43 billion: Cash personal loans.

- Balance: Purpose loans + revolving credit lines.

- 2023 full year: ~PLN 19–20 billion consumer loans (+20% vs. 2022).

- NBFIs now account for a significant share of new small-loan origination, especially where banks pulled back.

Loan Characteristics

- Payday loans: 30-day, a few hundred PLN.

- Installment loans: Up to ~PLN 50,000, repaid over months/years.

- APR evolution: From 100%+ (pre-cap) → ~45% of principal max cost.

- Customer base:

- Borrowers excluded from bank credit.

- Irregular income, gig workers, or urgent liquidity needs.

Major Players

Top 10 lenders now dominate volumes after consolidation.

Many smaller “parabank” lenders exited post-2016 and post-2022 caps.

Foreign & Institutional Investment

- Foreign-backed lenders: Provident (UK), Vivus (Latvia), Ferratum (Finland), Optima (Spain).

- Funding sources:

- Cross-border P2P platforms (e.g., Mintos).

- Equity + private debt (post-2022 bond issuance ban).

- Trend: Strong foreign capital inflows, but tighter margins.

2. Leasing (Consumer & SME)

Market Scale

- 2023: >PLN 100 billion financing (record high).

- Split: ~87% leases, 13% loans.

- Poland = 5th largest leasing market in Europe (2022).

- Finances ~50% of private investment in vehicles & equipment.

Segment Structure

- Dominant: Vehicle & fleet leasing (passenger + commercial).

- Other: Machinery, IT, medical, SME-focused equipment leasing.

- Consumer auto leasing is growing (0% finance deals, high car prices).

Major Players

20 members of the Polish Leasing Association (PLA).

Funding sources: Bank credit lines, ABS, and bond issuance.

Investment Angle

- Lower risk than consumer loans (asset-backed).

- Strong demand from SMEs (≈69% of clients).

- Portfolio size >PLN 200 billion → mature, liquid market.

3. Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL)

Market Scale

- 2024–25 volume: ~$1.5–1.7 billion (~PLN 6–7 billion).

- 9 major providers active by end-2023, reporting to BIK.

- Growth driven by e-commerce expansion.

Key Players

Business Model

- Merchant-fee driven (0% consumer APR for short tenors).

- Longer-term (6–12 months) may include a consumer fee/interest.

- Target group: Younger (<35), ~60% female, non-credit-card users.

Regulation

- EU Consumer Credit Directive (CCD) to cover BNPL in 2024–25.

- Poland: BNPL providers already reporting to BIK.

- Longer tenors are subject to anti-usury cost caps.

Investment & Risks

- Receivables funding via debt facilities or portfolio sales.

- Short-term, small-ticket → good performance so far.

- Credit risk: Thin-file borrowers, but mitigated via bureau checks & merchant recourse.

4. Car Loans and Auto Financing

Market Size

- Vehicle financing ≈ 40–50% of leasing/loan flows to SMEs in 2023.

- Growing reliance on loans/leases as car prices rise.

Market Structure

- New car financing: Primarily bank/captive lenders.

- Used car financing: Specialised non-banks and fintech platforms.

Key Providers

Otomoto Pay integrates instant auto-loan offers on Poland’s largest online auto marketplace.

Investor Angle

- Secured by vehicle collateral.

- Yields:

- Prime loans: 5–10% APR.

- Non-prime: Low-to-mid teens APR.

- Risks: Vehicle depreciation, repossession delays.

- Strength: High recovery values, strong demand for cars.

Summary

Poland’s NBFI sector spans cash loans, leasing, BNPL, and car loans, with each segment offering distinct scale, risk, and investment profiles:

- Cash loans - high-yield, foreign-backed, consolidating under tighter regulation.

- Leasing - mature, bank-linked, lower-risk, SME-driven.

- BNPL - fintech-led, fast growth, under regulatory expansion.

- Car loans - mix of bank/captive prime lending and non-bank subprime plays.

Together, these segments illustrate a diverse ecosystem, where private credit investors can access secured and unsecured opportunities across consumer and SME finance.

Major Players and Investment Activity by Segment

Poland's private credit market is characterized by diverse institutions operating across various segments, each with differing levels of investment engagement.

The following outlines each product area, highlighting key players, ownership structures, and funding trends.

Cash Loans

Dominated by firms such as:

- Provident Polska (UK-owned, International Personal Finance)

- Vivus / 4finance (Baltic-owned)

- Wonga.pl (acquired by Kruk, Poland)

- SMS Kredyt / Net Credit

- Creamfinance (Lendon)

- LoanMe and others

Key points:

- Foreign ownership is prevalent, with groups relying on parent capital or historical bond issuance.

- Provident obtained a Polish payment institution license to expand digital lending capabilities (Reuters).

- Institutional investment is high: international groups, local investors like Kruk, and P2P platforms all actively fund this space.

Leasing

Led by bank-owned lessors: PKO Leasing, Pekao Leasing, Santander Leasing, mLeasing (mBank), ING Lease, BNP Paribas Leasing.

Other players include captives like Volkswagen FS, Toyota FS, and independents like EFL.

Key points:

- Institutional investment is moderate, mostly via parent banks.

- Some firms issue bonds or ABS purchased by institutional investors.

- The Polish Leasing Association reports rising market share of the largest players, signalling consolidation (trade.gov.pl).

Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL)

Key players:

- PayPo (Polish fintech)

- Twisto (Zip)

- Klarna (Sweden)

- Allegro Pay (embedded in Allegro, Poland’s largest e-commerce platform)

- Banks: PKO BP, mBank (offering in-house BNPL options)

Key points:

- Institutional investment mainly comes from venture capital and strategic acquisitions.

- Examples include funding rounds for PayPo and Zip’s acquisition of Twisto.

- As receivables grow, BNPL firms may increasingly seek bank credit facilities or debt-fund partnerships.

Car Loans

Key players:

- Captive finance companies: Toyota FS, VW FS, Renault RCI Banque

- Specialised consumer banks: Santander Consumer, Alior Bank (auto unit)

- Non-banks: Mogo (Eleving Group), fintech platforms like Otomoto Pay, Smartney

Key points:

- Institutional investment varies: captives rely on parent groups, while independents turn to private debt and P2P investors.

- Example: Mintos investors fund Mogo’s Polish loans.

- Partnerships are emerging: insurers and pension funds investing in auto lease ABS for steady returns.

Cross-Segment Trend: Marketplaces and Global Capital

- Marketplaces like Mintos connect Polish loan originators (consumer and SME lenders, factoring firms) to foreign investors.

- This model means both retail and institutional investors abroad provide funding.

- Investors typically earn low double-digit yields, while originators manage origination and servicing.

The result: Poland’s private credit investor base is now internationalised, moving beyond reliance on local bank credit or bond markets.

Market Risks, Regulatory Changes, and Consumer Protection Trends

The Polish private credit market offers high growth and yield but faces notable regulatory, macroeconomic, and credit risks.

1. Regulatory and Compliance Risks

Key Changes

Investor Implication: Careful due diligence is essential; non-compliance (e.g., inadequate creditworthiness checks) could void loans and expose investors to losses.

2. Credit Risk and Over-Indebtedness

Consumer Segment

- Fast loan growth: Q1 2024 NBFI loans grew +113% YoY (Dudkowiak).

- Over-indebtedness risk: Rapid expansion raises questions about underwriting standards.

- KNF enforcement: Positive credit assessments & BIK reporting are now mandatory, but still new.

- Regional lessons: In other markets, caps pushed lenders to riskier borrowers, causing NPL spikes.

SME Segment

- SMEs moved from banks to NBFIs after credit tightening.

- Portfolios may carry higher inherent risk.

- Mitigant: Leasing and auto loans are collateralised → losses are less severe.

Investor Implication: Elevated risk in unsecured lending; secured assets (leasing, car loans) remain more resilient.

3. Macroeconomic and Funding Risks

Investor Implication: Funding agreements should include protections (collateral, triggers, diversification).

4. Consumer Protection Trends

- Anti-usury law: Tight cost and fee caps.

- Credit holidays (2022–2023): Mandatory relief for mortgage borrowers → sign of political willingness to intervene.

- UOKiK enforcement: Active fines for unfair clauses and misleading ads.

- KNF inspections: Direct oversight expected to consolidate weaker lenders.

- EU Consumer Credit Directive (2021/2023): Coming by 2024–2025 → applies stricter creditworthiness and disclosure rules across BNPL and other credit products.

Investor Implication: The “wild west” era of outsized payday-loan profits is ending, but a more transparent and investable market is emerging.

5. Outlook

Short-term: Some lenders will exit; loan volumes may dip.

Medium-term: Survivors will be stronger, more compliant, and better capitalised.

Long-term: Market transitions into a sustainable, investor-friendly ecosystem.

Opportunities for Private Credit Investors in Poland

Despite tighter regulations, Poland remains an attractive market for private credit investment, given its sizable credit gaps and high yields relative to Western Europe.

Below are key opportunities and strategies:

1. Financing Established Non-Bank Lenders

- Many leading consumer finance companies (Provident, Creamfinance, etc.) and fintech lenders need alternative funding, as they can no longer issue public bonds.

- This creates opportunities for private credit funds, family offices, and P2P platforms to provide:

- Bilateral loans

- Credit facilities

- Loan portfolio purchases

- Risk mitigation: Secured structures such as pledges on loan receivables.

- Expected returns: Low-teens annual yields in PLN for senior funding.

- Example: Mogo’s partnership with Mintos to fund car loans in PLN.

2. Investing in Lending Platforms and Originators

- Poland has a growing fintech lending scene – including digital SME lenders, invoice-financing platforms, and multi-lender marketplaces.

- Opportunities include:

- Equity stakes in high-growth originators

- Co-funding loans via platform structures

- Multi-lender funds (e.g., Montis/Kilde model in Mongolia applied to Poland)

- Factoring sector: Over PLN 45 billion in receivables turnover in 2023.

- Offers short-term, self-liquidating assets with lower default risk.

3. SME Private Debt and Leasing Funds

- Potential strategies:

- Finance smaller independent lessors or credit unions.

- Provide mezzanine or subordinated debt for portfolio growth.

- Direct SME lending (equipment loans, sale-and-leaseback).

- Returns:

- Mid-single digits for senior-secured leasing finance.

- 8–12% for SME private debt, secured by equipment or receivables.

- Supported by:

- EU recovery funds

- Stable macro outlook fueling SME investment.

4. Buyouts and Consolidation Plays

- Tougher regulations will drive industry consolidation.

- Private equity opportunities:

- Acquire smaller loan companies or loan books.

- Inject capital to meet PLN 1m minimum capital requirements.

- Roll up regional firms into a larger, efficient platform.

- Exit strategies:

- Sale to a strategic

- IPO (leveraging Poland’s large 38m domestic market).

5. High-Yield Consumer Loan Portfolios

- Options for higher-risk investors:

- Purchase consumer loan portfolios at discounts.

- Co-invest with debt collection firms (e.g., Kruk, Best) in restructuring.

- Distressed debt funds can benefit as the credit cycle turns.

6. Risk-Adjusted Returns

Expected return spectrum for private credit in Poland:

Many foreign investors hedge PLN exposure or invest via EUR-denominated structures.

PLN has been historically stable compared to its peers, making unhedged yields attractive.

7. Mitigating Factors

Use Poland’s infrastructure for risk control:

- BIK credit bureau data for due diligence.

- Legal enforceability through efficient courts and collateral pledges.

- EU/State guarantees (e.g., BGK de-risking for SME loans).

Conclusion

Poland offers private credit investors a blend of developed-market stability and emerging-market returns.

The regulatory reset, while challenging, professionalises the sector and reduces extreme risks.

Investors who partner with compliant, innovative originators in consumer finance, leasing, BNPL, or SME lending can tap into Poland’s large unmet financing needs.

With strong economic fundamentals, EU integration, and cautious banks, private credit is growing in Poland’s financial ecosystem.

It offers attractive yields and developmental impact.

Sources

- European Commission. Economic Forecast for Poland. Brussels: Directorate‑General for Economic and Financial Affairs, May 2025. https://economy‑finance.ec.europa.eu/economic‑surveillance‑eu‑economies/poland/economic‑forecast‑poland_en (accessed 12 June 2025).

- Eleving Group. “Eleving Group (Mogo) – Lending‑Company Profile.” Mintos (lending‑marketplace website). Last updated 23 April 2024. https://www.mintos.com/en/lending‑companies/mogo (accessed 12 June 2025).

- International Personal Finance plc. Annual Report and Financial Statements 2023. Leeds: IPF, 14 March 2024. https://www.ipfin.co.uk/content/dam/ipf/corporate/documents/investors/annual‑report‑/2023/annual‑report‑2023.pdf (accessed 12 June 2025).

- Legal 500. “Oversight of Lending Institutions by the Financial Supervision Authority (KNF).” Legal Developments (Thought‑Leadership series), 3 January 2024. https://www.legal500.com/developments/thought‑leadership/oversight‑of‑lending‑institutions‑by‑the‑financial‑supervision‑authority‑knf/ (accessed 12 June 2025).

- Narodowy Bank Polski (NBP). “Interest Rates – MPC Decisions.” Warsaw: NBP, 8 May 2025. https://nbp.pl/en/monetary‑policy/mpc‑decisions/interest‑rates/ (accessed 12 June 2025).

- ———. “Press Release from the Meeting of the Monetary Policy Council Held on 5 October 2022.” Warsaw: NBP, 5 October 2022. https://nbp.pl/en/press‑release‑from‑the‑meeting‑of‑the‑monetary‑policy‑council‑held‑on‑5‑october‑2022/ (accessed 12 June 2025).

- Poland. Ustawa z dnia 6 października 2022 r. o zmianie ustaw w celu przeciwdziałania lichwie (Act Amending Laws to Counter Usury), Dz.U. 2022, poz. 2339.

- Statistics Poland (GUS). “The Statistics Poland Information on the Updated 2021–2022 Quarterly GDP Estimate.” Press release, 20 April 2023. https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/national‑accounts/quarterly‑national‑accounts/the‑statistics‑poland‑information‑on‑the‑updated‑2021‑2022‑quarterly‑gdp‑estimate,5,11.html (accessed 12 June 2025).

- ———. Gross Domestic Product in 2023: Preliminary Estimate. Warsaw: GUS, 31 January 2024. (PDF). https://stat.gov.pl/.../gross_domestic_product_in_2023_preliminary_estimate.pdf (accessed 12 June 2025).

- Waszak, Marcin. “Loan Institution in Poland.” Dudkowiak, Kopeć & Putyra Legal Blog, updated 23 August 2024. https://www.dudkowiak.com/fintech‑in‑poland/loan‑institution‑in‑poland/ (accessed 12 June 2025).

- World Leasing Yearbook / Związek Polskiego Leasingu. “O leasingu w Polsce w World Leasing Yearbook 2025.” Warsaw: ZPL, March 2025. https://www.leasing.org.pl/O+leasingu+w+Polsce+w+World+Leasing+Yearbook (accessed 12 June 2025).

- Bank.pl (Mórawski, Karol). “Już niemal 2 mln Polaków skorzystało w ubiegłym roku z zakupów BNPL.” Bank.pl, 31 January 2024. https://bank.pl/juz‑niemal‑2‑mln‑polakow‑skorzystalo‑w‑ubieglym‑roku‑z‑zakupow‑bnpl/ (accessed 12 June 2025).

- EY Polska. “Instytucje pożyczkowe pod lupą – co zmieniła nowa ustawa antylichwiarska?” EY Insights, 2023. https://www.ey.com/pl_pl/insights/miesiac‑prawa/ustawa‑antylichwiarska (accessed 12 June 2025).

- Rzecznik Finansowy. Maksymalna wysokość pozaodsetkowych kosztów kredytu (conference presentation), 21 March 2023. https://rf.gov.pl/wp‑content/uploads/2024/04/Prezentacja‑koszty‑kredytu‑21.03.2023.pdf (accessed 12 June 2025).

- Urząd Ochrony Konkurencji i Konsumentów (UOKiK). Raport z działalności UOKiK w 2023 roku. Warsaw: UOKiK, 2024. https://uokik.gov.pl/Download/735 (accessed 12 June 2025).

Disclaimer Notice

This page is provided for general informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, financial, or investment advice. Please refer to our Full Disclaimer for important details regarding eligibility, risks, and the limited scope of our services.

FAQ

Poland’s private credit penetration (~35% of GDP) is lower than in the Czech Republic or Hungary, but higher than in some frontier markets. This under-penetration offers structural growth potential, while EU membership and stronger institutions provide investors with greater legal certainty than in less regulated neighbours.

International investors are highly active — through foreign-owned NBFIs (e.g., Provident, Vivus), global P2P platforms (Mintos, etc.), and cross-border private credit funds. This global capital flow both diversifies funding and integrates Poland into international investment channels, making it less dependent on local banks.

Leasing and auto finance tend to be more resilient because loans are secured by collateral such as vehicles or equipment. By contrast, unsecured consumer lending (cash loans) is more vulnerable to defaults during economic stress, though it compensates with higher yields. BNPL remains relatively new but benefits from merchant recourse and shorter loan tenors.

Poland has a large population of 38 million, with a growing base of younger, digital-first borrowers. Strong e-commerce adoption fuels BNPL, while rising wages and a tight labour market sustain consumer credit demand. Additionally, the influx of Ukrainian workers has expanded the borrower base, particularly in the lower-income and flexible-work segments.

Exit routes include selling loan portfolios (e.g., to debt collectors like Kruk), trading structured ABS backed by leases or loans, or strategic acquisitions by larger financial groups. In some cases, consolidation could lead to IPO exits on the Warsaw Stock Exchange, particularly for scaled lenders or fintechs.

.avif)